The stories we tell

Picture the horrific scene… a young African boy cowers in the undergrowth as his mother is brutally murdered in a raid on his village. Despite being persued by the assailants, he manages to escape; he runs and runs, far from the village and navigates ordeal after ordeal; finally, thanks to incredible resilience, like many refugees of war, he washes up in a European city, penniless and friendless. But despite his traumatic experiences, he is fascinated and inspired by his new urban environment. By a remarkable stroke of luck, he secures the patronage of a wealthy sponsor and receives a lavish western education. He reaches adulthood among his white benefactors, and begins to feel increasingly at home. He never forgets his simple village life however, and one day, he bumps into some members of his tribe who have also, unbeknown to him, made the journey. They persuade him to return home where he is fêted as the new village chief. Contrary to the polygamy that is the norm in his village, he takes but one wife; and he governs with wisdom, benevolence and unstoppable optimism. He judiciously transitions his people from a crude agrarian subsistence to a modern, developed lifestyle, securing investment in transport infrastructure, housing, healthcare systems and cultural facilities. They adopt Christian festivals.

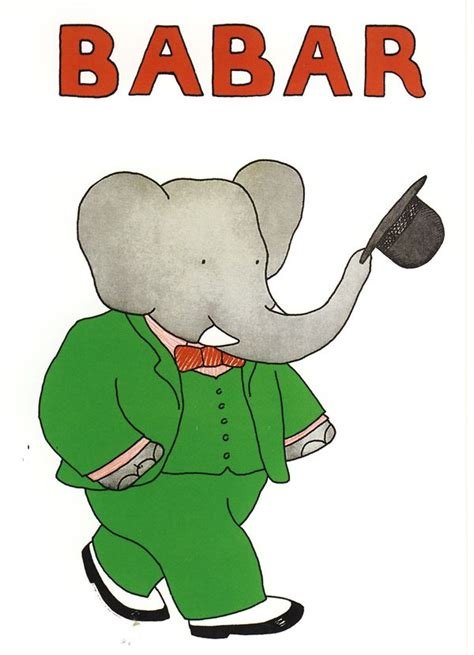

This compelling tale is of course, that of Babar the Elephant, the 1934 creation of Jean de Brunhoff (or more accurately, of his wife Cécile.) The grand European city in which the little elephant finds himself, with its boulevards and cafés, is unmistakeably Belle Epoque Paris, and his circle of friends, high society bourgeois.

Our 6 year old son can’t get enough of these charming stories; I haven’t the heart to tell him (yet!) that the underpinnings of the Babar narrative might be seen as rather dubious.

As Thomas Piketty points out in his brilliant Capital and Ideology, foreign financial investments grew enormously during the four decades of the Belle Epoque period; the share of France’s total capital wealth represented by such investments rose from 6 to 21%. Moreover, as if to underline the moral appropriateness of these endeavours, much of this investment in the Belle Epoque period was government guaranteed. And it was safeguarded with colonial military force. In 1870, only 10 percent of Africa was under formal European control; by 1914 this had increased to almost 90 percent of the continent. It’s entirely likely that the fortunes of the kind old lady and the prestigious friends to whom she introduces young Babar were, in significant part, based on colonial exploitation of one sort or another. A key thrust of Piketty’s work is that throughout history, the deep inequalities that have tended to divide humanity have not simply “happened” or emerged out of technological conditions; rather, they have been legitimised and held in place by the creation and assertion of powerful ideologies. Europe’s late 19th Century scramble for Africa was framed not just as a violent quest for resources and open markets, but as a civilising mission. Piketty’s work proposes the perennial existence of such legitimising ideologies from early ternary societies through to the present day.

The world’s current travails have shone a bright light on inequalities (of wealth, access to adequate healthcare and life expectancy) within and between societies; and his book – about how culture finds strategies to justify inequalities – will surely become a key starting point for the debates to come in the new era. Debates which will, in one way or another, matter to how and what brands communicate. It’s well worth reading. For a brief taste, see here, or alternatively, read a few Babar stories; they melt the hardest of hearts…